After the student massacre in 1976, many believed that the era of student movement in Thailand came to an end. However, in recent years, many student groups from various regions are now attempting to solve various problems in Thai society once again. In Part I of Modern Thai student movement, the writers explore the history of Thai student movement and how this generation of student activists view themselves and their fellow students.

Nonetheless, it has become clearer that the new military regime’s reform policies and proposed bills on various issues, such as education, energy, natural resources, land reform, forestry, immigration, education and tax, will benefit some groups of people while negatively affecting others. NGOs and political activists have begun to challenge the junta once again despite the imposition of the martial law, which gives the regime unprecedented power to make arrests over any expression of anti-coup opinion. In November, five student activists from the Dao Din group of Khon Kaen University in the Northeast, gave the three-fingered salute to Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader. The students were immediately detained and later interrogated by the military. The military also involved their parents and threatened to have them fired from the university if they did not accept the junta’s conditions. Although the junta might expect the harsh treatment and intimidation of the Khon Kaen students to serve as a lesson to keep other young activists at bay, the result was the opposite.

One after another, despite the presumption that the era of Thai student movement ended with the bloody student massacre of October 1976, student activists of various political orientations began once again to voice opposition to the suppression by the junta. Although these new student movements are not mass youth movements affiliated with political ideologies as in the 1970s, neither are they affiliated with the current colour-coded political divide in Thailand. These young activists began to engage in many regional and national problems despite the obstacle of the martial law. To look into the history, dreams, and aspirations of these student activists, who are now at the forefront of Thailand’s political mobilization, Prachatai introduces the series “The Modern Student Movement,” by Emma Arnold and Apisra Srivanich-Raper.

Five members of Khon Kaen University student activist group, Dao Din, flash three-fingered salute in protest against the junta in front of Prayut Chan-o-cha, the junta leader, during his speech.

Part I:

The student uprising of 1973 played a critical role in pushing out a repressive military dictatorship and heralding in a new democratic era in Thailand. Renowned political theorist Benedict Anderson calls the student movement of that time “the driving force” behind a series of political and social reforms. Students became active in labor movements, formed farmer networks, and traveled to rural areas to learn from the marginalized.

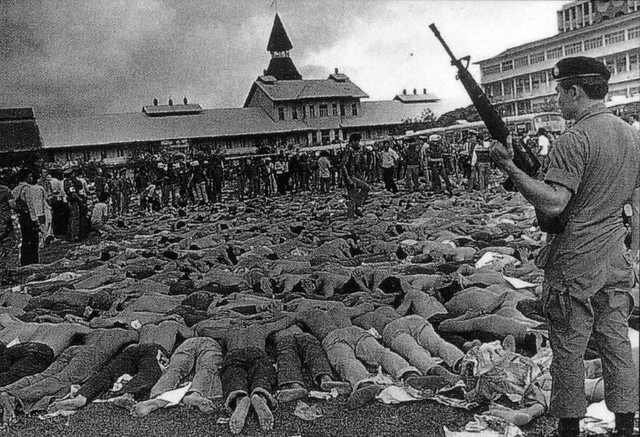

The brutal student massacre of 1976 crushed the movement and shook the nation. Forty years later, student activism in Thailand seems to be just a shadow of what it once was. Or is it still alive? An article from The Nation newspaper in Bangkok recently reported that student activism is being revived.

But there is a lot working against student activism. Palagoon Poonklang, an activist student and member of the Phuan Sangkhom at Mahasarakham University, says, “As a student that participates in political movements, I am in the minority of students. The environment of the university doesn't encourage students to be politically engaged,” he asserts. “This environment just forces them to study, only to study.”

But Dr. Buapun Promphakping, a professor from Khon Kaen University’s Faculty of Social Development, believes that the blame should not rest solely on the universities.

“I would have to say that the disengagement is on the students’ side rather than administration or the state’s side,” he explained, “thirty years ago we thought of students as intellectuals. In this era, this is no longer true.”

Students have seemingly been absent from recent political protests, where thousands of people have taken to the streets in support of each the Red and Yellow Shirts. But they have been visible in other ways.

At universities across the country, student activists groups have formed around a variety of interests and goals. Some groups engage in traditional political spheres through activities such as petitions and protests; others approach politics less directly— working on grassroots social development projects, challenging conventions at their universities, and increasing political awareness through education.

The following is a selection of voices of the modern student movement. We spoke to nine student groups at universities in Northeast Thailand about their work, their beliefs, and their hopes. Through these discussions, it is possible to approach the questions of whether students should or should not have a role in politics, what motivates them, and why they have generally avoided defining themselves as red or yellow.

Student forced to lay down facing the ground during the student crackdown in Thammasat University, which later turned into a brutal massacre on 6 October 1976

The Tamed Generation

Soom Giew Dao (ซุ้มเกี่ยวดาว), Khon Kaen University

Affiliation: Independent, Members: 20 members

“You have to understand,” stated Patiwat Saranyaem, “Khon Kaen University limits students. The university doesn’t support them working on any political movements or issues at all.”

Mr. Patiwat is a member of the student group Soom Kiew Dao, or “Harvesting the Stars”.

Members of Soom Kiew Dao are united in the common goal of supporting democracy.

When discussing the group’s work, Mr. Patiwat speaks of collaboration with a variety of Red Shirt organizations in the area but is hesitant to identify his group as such. “Right now it is only the Red Shirts who are building a movement for democracy,” he explained. “Our side, we work to support democracy”.

From a family of political activists in Sakon Nakhon Province, Mr. Patiwat is certainly not shy when it comes to sharing his opinions. He speaks with exuberance, filling the small room with his boisterous voice.

To Mr. Patiwat, fighting for democracy means fighting for the rights of those who are oppressed. He believes that KKU was founded as an undemocratic system of oppression. “KKU was originally established to produce students for labor, not to train students to use their brains,” Mr. Patiwat attests, “KKU was set up to control the Isaan people.”

He goes on to explain that KKU was established in the 1960s under the national government’s first Social and Economic Development Plan. The university’s first two faculties were agriculture and engineering, grooming students to become part of the county’s growing industrial sector. To this day, the university doesn’t have a faculty of political science.

As a result of this, Mr. Patiwat explains, “now KKU students are not interested in social or political issues and they don’t care about history. This is because of the control of the government.”

He laughs, “They don’t have to think about anything. They just eat, shit, sleep, and don’t care about anything.” Students are required to participate in university activities, such as sports events and religious and cultural activities under the school’s Integrated Learning Program. This program was introduced by the university administration in 1989 to better prepare students for their future careers, but Mr. Patiwat describes its requirements as “rituals to control people.”

“Students are tamed by what they study and learn in the educational system. In this way they are tamed and controlled by the conservative elites,” Mr. Patiwat said.

Soom Kiew Dao works to teach what is not taught in school, focusing on political history and working with communities to build local knowledge. Within the group, members regularly exchange books. The fact that some of these books have been censored by the central government makes them all the more important.

When asked about his hopes for the future educational system in Thailand, Mr. Patiwat’s answer is simple and immediate. “I want [the university] to stop controlling students and preventing students from asking questions,” he responds.

He pauses to think for a second before continuing. “I feel it is a shame because I want to be able to say something more, but what I am telling you is ‘please stop preventing students from asking questions’.”

The Thai modern student movement to be continue on Part II

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”