Updates on the situation of the anti-establishment Red Shirt supporters in the North and Northeast, 2015: how their ways of thinking and living have changed since the 2014 military coup

“Red Shirts” is a well-known term in Thai politics referring to groups of people who share a similar ideology, yet it also includes people from a spectrum of political ideologies. They include supporters of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, the Pheu Thai Party, supporters of the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), several autonomous anti-establishment red-shirt groups, individuals in activist and intellectual circles, and many more who may not identify themselves as “Red Shirts” per se but share certain fundamental ideas with the other groups. Despite these differences, the Red Shirts’ power base is presently outside of Bangkok. As the Red Shirts’ struggle has been going on for many years, Prachatai felt it was important to offer readers an update on their situation, through interviews with members of different groups based in the provinces of Maha Sarakham, Ubon Ratchathani, and Chiang Mai.

Clothes line and a rice field at a red-shirt village in northerastern Thailand

The Red Shirt leaders who Prachatai got to talk to in these areas come from diverse backgrounds. In fact, a majority of them have just been “born into politics” – meaning that they became interested and started to take an active role in politics only between 2009 and 2010. Before that, many of them voted for the Democrat Party or other political parties but never Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai party.

After the 2006 coup, many of these leading groups did not immediately come out to protest against what had happened. They were rather in a state of “Let’s wait and see. Let’s listen to what different sides have to say first”. Others decided to come out right away to protest against the junta but were only able to mobilize small numbers, with their main activity being the distribution of leaflets. Some were well-respected ‘old leftists’, who believed that the new power groups, such as the Thaksin group were less threatening than the established elites. Some of the leaders we interviewed were happy to have their names disclosed while others preferred to stay anonymous.

Another interesting aspect Prachatai found is that there are similarities as well as differences between these Red Shirt groups in terms of their origins and operations – something we, as outsiders, may hardly know about. Yet these interviews are far from representative of the movement as a whole; rather they are pieces in the jigsaw of a larger picture.

1. Intense military control of areas in different provinces after the 2014 coup

After the 2014 coup Red Shirt leaders have been under the strict military control. Some of them have been summoned by military order for “attitude adjustment”. Some were detained in military camps for a few days while others were detained for seven days. Some have been repeatedly summoned, especially if their presence was spotted at political events, even though they might not have been the event organizers themselves. Among the leaders in some areas such as Ubon Ratchathani, who would typically draw huge crowds, four to five still have to report to the military every Monday. There are also activists whose names are on the military’s “attitude adjustment” list, and who are required to inform the military in advance of any public seminars they are going to hold, or seek their permission if they wish to travel abroad. In the latter cases, they are required also to report to the military every time they come back to the country, with airport immigration officials told to check and copy every single detail in their passports to see which places they have travelled to, and whether they were given permission to travel to those places. Yet, according to the interviewees, none of them said they were intimidated or abused by the military.

Just after the military took power, a large number of Red Shirt leaders were on the run or in hiding as they feared for their safety. In Ubon Ratchathani and Chiang Mai there was a phenomenon of “taking hostages” – that is, if the army could not find the persons they were looking for, they would detain family members of Red Shirt activists in military camps so that the targeted activists would come out from hiding and hand themselves in.

2. Knowing the origins and backgrounds of Red Shirt groups in different provinces and their political stances

Maha Sarakham – Only time will tell: the second and third generations of leaders

From left, "Yao" and Khaikhoei Chanpleng

Khaikhoei Chanpleng, one of the leaders in Maha Sarakham, stated that he and others have taken on a leadership role after the government crackdown on Red Shirt demonstrators in 2010. Not only did the crackdown see the Red Shirts badly defeated, but it also saw, subsequently, the widespread emergence of various Red Shirt groups or factions in the northeastern provinces. Some broke away from the larger groups. Some were new with their own particular characteristics. Some are affiliated with the UDD. There are also those who have adopted the slogan of “Love Thaksin” yet remain autonomous as a group and dare to remain critical even towards those on the same side.

Khaikhoei works together with another leader of the group, identified merely as Yao. According to Yao, when the mass Red Shirt demonstrations led by the UDD first took place in 2010, they did not yet know each other. But just like many other ordinary demonstrators, they often went on their own motorbikes to gather at the provincial hall – the main protest site in Maha Sarakham – to listen to speeches, and that was how they got to know each other. Later, after the crackdown, Khaikhoei and others were arrested and charged with burning down the provincial hall. In fact the only damage done was to a tamarind tree, and a telephone box outside the hall, rather than the actual building. Tires were also burned on the footpaths. After 8 months in jail, he was found not guilty and eventually acquitted.

Thaksin as a “symbol of awakening”

“We are not doing it for the (Pheu Thai) party or for Thaksin. We are doing it for the masses, for our children and grandchildren. We have lost our rights and liberties. We have lost our democratic system. You must ask yourself, ‘how in 80 years [since the forced change from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy] were we able to have democracy for only seven years?’ I can tell you I’m not doing it for you but for your children. Well, even for your children, it might not be in time,” said Khaikhoei.

When asked about Thaksin, he replied “I’m not disappointed with Thaksin as there’s nothing to be disappointed about. And I’m not naive about him either. People in Isaan like him but they are not naive. The reason why people here are happy to help him is because we think we – the people – could rely on him”.

He continued by giving some concrete examples of Pheu Thai’s policies.

Similarly, according to Yao, “(Thaksin) is a symbol of awakening. Without him, we would not have been where we are today. People would not have been able to be better off financially. In my opinion, however, he’s still not fighting hard enough. He is still worried about his own interests. If he is not worried about his own interests.”

Supporting a primary vote: Pheu Thai must listen to people’s demands!

The only criticism this Red Shirt group in Maha Sarakham has made against the Pheu Thai Party is that the MP candidates it puts forward are often not who the people want. Without doubt, the group still votes for Pheu Thai MP candidates in elections. The group thinks that the party should set up a system, which takes into account people’s preferences for MP. However, whilst many villagers agree with such an idea, no one has really pushed for it to happen.

When asked why they disliked some Pheu Thai MPs, Yao responded: “It was difficult for people to have access to them. Every time we go, it’s always the wife who comes out and says the MP is not there. The way the wife talked to us is just like a queen. We, the people, don’t seem to matter much in their eyes.”

Loss of faith in the UDD and in “non-violence”

Khaikhoei and Yao went on to criticize the UDD heavily, both in terms of their strategy and leadership structure.

“Are we discouraged at all? Every time we fight, we face the same thing over and over again. And all they say is to use non-violence, non-violence, and non-violence. We have used and experimented with it before and it always ends up with us being killed,” insists Khaikhoei.

“At the red-shirt demonstration at Aksa, actually we did not agree with the idea of going to Aksa. We held a meeting and thought that it would be better for us to organize demonstrations in our own provinces. But then the UDD decided to hold a rally there and people thought that if we gathered there, nobody would dare to disperse us (as it is located near the Crown Prince’s Palace – translator). When the villagers saw the rally on television, they wanted to go. They pushed us to go with them. As leaders, we had to respond to the villagers’ demand, so we had to go,” said Yao. She also added that a large number of her fellow villagers still mainly listen to the key (UDD) leaders. But for her, the UDD leaders at the local level are “not that great anymore”. She also insisted that the UDD should change its management structure since its leaders with decision-making power often come from outside Isaan while the majority of Red Shirts, who make up the bulk of the UDD, are Isaan villagers.

If we are to ever take to the streets again, it must be only for a real change

One of the leaders in Maha Sarakham Province works quietly with his small group. Not much detail was revealed. He seems to be highly cautious and his way of thinking tends to be similar to that of the old leftists who joined the now-defunct Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) in the late 1970s, though he has become interested in politics only in recent years. After the 2006 coup, he was still at the stage of “let’s listen to different sides first in order to analyze the situation.” But once he came up with his own analysis and joined the Red Shirts, he began to study Thai political history, from the Boworadet Rebellion and the 1932 Revolution onwards, as well as the history of people’s revolutions in other countries.

“We don’t want quantity but quality – those with 100 per cent firm ideology and a clear mind”. He described the group’s approach thus, before adding that his group wouldn’t criticize different approaches from other Red Shirts. He also said if there is ever another Red Shirt demonstration, he himself and his group would, however, not take part unless it leads to a real change.

“The UDD won’t get anywhere since if they’re only aiming at reform, at an election; we would end up being in the same old cycle of ignorance and blindness. Some villagers also agree. They say they don’t want this anymore; the aim is too low.”

The “Chak Thong Rob” (or the People’s Warrior Alliance): a large-scale Red Shirt coalition and pride in “Isaan, our home”

Ajarn Toi, leader of red-shirt Chak Thong Rob group

Chak Thong Rob is another Red Shirt group, based in Ubon Ratchathani, with a large number of supporters. It is led by a man identifying himself as Ajarn Toi whose life experiences differ starkly from many other leaders in the region. As a rich businessman, he lived in many countries before deciding to give that up to look after his mother back in Issan. As he is Isaan-born, he holds a very strong sense of regional identity. He feels that Isaan people, even though they make up the largest regional population in the country, have always been oppressed and looked down upon throughout Thai history. Therefore, he would like to restore not only the history of the Isaan people’s movements, which can be traced back to the Phu Mi Bun Revolt (also known as the Phi Bun Revolt) in 1902, an uprising of Isaan people against the rule of the Chakri Dynasty but also to the local yet unique languages of the region. With his Isaan pride, he also said this was actually the first time he had agreed to give an interview in the language he sarcastically called “Bangkok Thai.”

Asking what made him become interested in politics, he responded: “It is in my DNA perhaps. Looking back 111 years ago, my grandfather was killed by Krom Luang Sappasit in the so-called ‘Phi Bun revolt’, in Trakan Phuet Phon District (north of Ubon Ratchathani),” Ajarn Toi said. He pointed out that since this was only two generations back, it was not difficult for such stories to get passed on.

“So we have seen unfairness and injustice since our grandmother and grandfather’s times,” he added.

His starting point as a Red Shirt leader was when he worked as a DJ for a community radio station, which had, as it turned out, helped him gain a lot of popularity. Initially the content of the programme was soft, restricted to anything one could think of for a radio talk show, like discussions about everyday life and so on. It was only some time later that his focus shifted to politics. Yet, no matter how passionate his political discussions often were, he was always careful that he did not get into trouble under Article 112 of the Thai criminal code or the lèse majesté law.

As his popularity increased, resource allocation became easier. A two million baht donation he received was spent on setting up two new radio stations, which also enabled the formation of his Chak Thong Rob group in 2007. By 2010 many members of the group had also joined the UDD. During the crackdown on large-scale protests that started that year in the heart of Bangkok and later spread to other provinces including Ubon Ratchathani, there were attempts to burn down provincial halls by protesters. Ajarn Toi became one of the accused. He was detained for 15 months in prison before being found not guilty, thus acquitted.

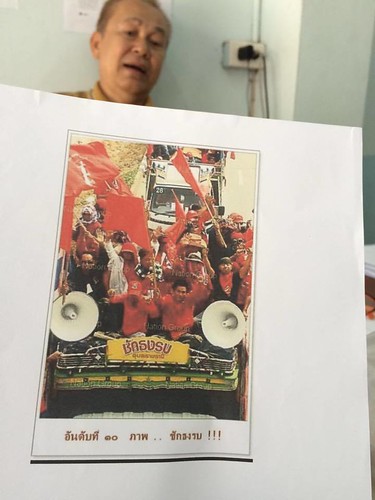

Ajarn Toi shows photos of the red-shirt caravan when the group traveled from Ubon Ratchathani to join the demonstration in Bangkok

“If you ask me whether people have changed at all? I think so. They have become more vigilant. I have seen it myself. I was imprisoned while my comrades got killed or injured. From just my group alone, almost 500 members were charged with burning down the provincial hall. Police made such indiscriminate and harsh allegations. Some families were split. Some went on the run. Some had themselves ordained as monks. Some fled to other countries. When Yingluck’s government was in power, we told them to withdraw all arrest warrants which had no back-up evidence, but they did nothing.”

Criticizing Thaksin amidst those who love him

“Our group is huge. In 2010 we were able to mobilize people to join the protests (in Bangkok), and we travelled in as many as one hundred buses. People also donated a lot of rice, which filled up an entire 10-wheeled truck. We were able to stay in Sanam Luang for a month without any problems. Don’t forget that Red Shirts are huge in numbers; some are terrible, some are good. Some Red-Shirt MPs even put their feet up while performing their duty in the Parliament – do you think that’s appropriate? Some of them were able to mobilize a lot of people and then tried to please Thaksin by calling him ‘master’ or ‘father’. I think that’s so pathetic.”

When asked how he managed to deal with those who loved Thaksin given that he also harshly criticized Thaksin and Pheu Thai, Ajarn Toi replied: “The villagers really do love Thaksin. It’s not that I don’t love him. But to love him doesn’t mean that we are his slaves. We can be fellow partners. When I see what is right, I say it. What I see something is not right, I also say it. Thaksin is not God. If I give my honest opinions, is it then my fault?”

Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan: the 3 districts of hardcore Red Shirts in Chiang Mai

The office of red-shirt Khon Rak Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan group which also runs a community radio station

Speaking of the “Red Shirt zones”, one would definitely think of Chiang Mai, particularly the three remote districts of Fang, Mae Ai and Chai Prakan. The group, called Khon Rak Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan (or ‘People who Love Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan’) was formed in 2007-2008. One of the group leaders is an ex-farmer who used to a member of the CPT in the 1970s. In 2010 when the UDD called for a mass demonstration in Bangkok, villagers in this area got together to organize a Buddhist ceremony in order to raise funds to cover transportation costs so that they could take part in the demonstration.

“We went (to join the protest in Bangkok) five to six times, using the funds we raised by ourselves. Once we managed to go in nine buses. The highest number was 20 buses for one trip. That was in 2010. At that time we already had some support from the MPs,” the leader said.

Fundraising through events such as Buddhist ceremonies, Chinese banquets, and musical concerts was so well-supported by the local villagers that the group had some money to spare for setting up a community radio station. The station was run under the slogan of “People’s radio station by people’s money”, with a broadcast range covering all three northern districts.

After the 2014 coup, just like any other community radio station, army personnel attempted to confiscate their radio transmitters. But unlike other stations, the group managed to keep its equipment. The station continues to operate at present. However when it comes to political issues, they have been reduced to merely reading the news, instead of having hard discussions.

Apart from these activities, the Khon Rak Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan group also operates a lottery to raise funds within the community. According to one of the group leaders, the reason why they were able to be the very first leaders who could sustain their leadership was because they tried to keep their financial system as transparent as possible. He explained that this includes setting up a committee comprising of members from different sectors to take care of financial matters.

Later the structure of the group expanded – very rapidly –with a committee for each district and each sub-district (the former comprised of 15-16 members). The purpose of this structure was to enable collective organization of local villagers, swift distribution of news and information, transparent and effective management of resources, and to provide assistance on various matters e.g. donations for people affected by big floods in the southern part of Thailand etc.

Accepting new conditions: villagers and leaders in a state of confusion

When asked about the local atmosphere, another group leader said that the current atmosphere is still something new and that they still do not know how to plan their strategies.

“To be frank, in this current situation, people are still afraid, they don’t know what to do. What we are facing right now is something new, we still don’t know how to handle it. We were not prepared for it. Villagers are in a state of confusion, so are the leaders. Different leaders say different things. Once they have learnt and understood where the main problems lie in, things will be easy. However, they are generally told to keep quiet.”

‘Dap Chit’ -- A Panorama of the Chiang Mai UDD

Not far from the city of Chiang Mai, Senior Sergeant Major Pichit Tamoon, also known as ‘Dap Chit’, one of the UDD leaders in Chiang Mai who coordinated with several groups in various districts, was adamant that the villagers had not changed.

“They are frustrated and unable to communicate. The media they consume is one-dimensional. They might have a Facebook or Line account, and primarily use them for media consumption. I’m not saying that these people lack critical thinking skills. However, the reliability of these media outlets is still questionable. Some information communicated via these channels is just rumour, which is dangerous for them.”

When asked about the development of the UDD in his area, he said that the seeds were sown since the case of Thaksin. From then on, the villagers began to comprehend the concepts of freedom, liberty, equality and fairness.

In 2010, a year after the formation of the Chiang Mai UDD in 2009, there was a UDD general assembly in Bangkok. The Chiang Mai UDD then started fundraising.

“At the time, there was no financial support from the main group. The group helped pay for petrol only after we had arrived. The villagers raised about 300,000 to 400,000 baht. They really wanted to attend the event.” He said that 2010 was the most fruitful year of the Chiang Mai UDD. There are 26 districts in Chiang Mai. Yet, there were more than 30 UDD groups in the province. In some districts, there were more than 3 groups; each group had different ideas regarding financial management – but not political ideology.

Big supporter of primaries

In spite of his role as a coordinator between various UDD groups, Dap Chit was not well liked among some Pheu Thai politicians. This is largely due to his demand that Pheu Thai Party hold “primaries” for their candidates.

“We had to accept the fact that 60-70 per cent of Red Shirts are Pheu Thai Party supporters. Those who long for social reform regardless of the political party in power might probably be about 20% of the Red Shirts in Chiang Mai. This is my guess-timate from those whom I have come across. Almost all leaders at the district level ally themselves with the Pheu Thai Party. Only a few of them don’t.”

“I give you one example. In 2011 I was heavily attacked – from all sides – for supporting primaries. The party was also not happy with me at all. In fact, this idea didn’t come from me. The very first person who mentioned it was Mr. Thaksin himself – that was in 1999 when the Thai Rak Thai party had just come into being. I just felt that in 2011 once the election was over, the Red Shirts had become nothing in the eyes of the party. Those who were given some importance were the 7 – 8 key Bangkok-based leaders. So this is why I think we need to give more power to the people.”

“My question is: why does the Pheu Thai Party have to monopolize its own people? It’s like we are fighting for equality and against injustice but it appears that there is nepotism within our own party. If the party can get rid of nepotism and adjust to serve the people better, it would be great. In terms of management, let it be dealt with separately. But when it comes to selecting MP candidates, the party must make sure that people are happy about it.” At that time, claimed Dap Chit, there was a huge support for primaries among red shirt people, especially those in Isaan, as they really felt frustrated with the current system of the party.

When asked about the possibilities of increasing that 20 per cent, he said that this kind of thing would come naturally. At the moment he often goes to visit the party’s canvassers. He said that these people have become increasingly interested in ideas such as transformation through non-violence, as well as rights and liberties.

3. Various approaches to the “waiting game”

Given this difficult situation facing these groups, what turned out to be the hardest question of all in these interviews was: what do the groups plan to do now? In response, one of the leaders of the Fang-Mae Ai-Chai Prakan group said: “What we can think of now is to sustain our collective forces. We, as a group, try to keep in touch. We meet on different ceremonial occasions. Now we also have this community welfare fund, in which some 3,000 of us are members. We still stick together.”

As for Khaikhoei, he explained: “We often meet on ceremonial occasions like merit-making events. Currently we are working with the elderly. We see that many of them are still far behind when it comes to knowledge about politics. If we work with them, they will be the ones who pass on their knowledge to their children. Additionally we also work with local Buddhist abbots. Here, monasteries have long played a supportive role in people’s movements. They have always helped organise charity events such as robe offering ceremonies and so on. If Thaksin were to owe somebody, the one to whom he owed the most would be the abbots.”

As for Dap Chit, he believed that speaking to local villagers is an important task. Even though they are already active politically, they still need “courage” to continue.

“We can’t do much at the moment. So we just do what we can. (If you) ask why I have to go visit the villagers every week, it’s because they need courage. They need someone to go and talk to them. They know everything but they just want somebody to talk to. Be it funerals, religious ceremonies, birthday parties, you name it, when they invite me to give a speech I always go,” said Dap Chit.

Among these Red Shirt leaders, the approach that Ajarn Toi follows is the most unconventional. This could perhaps by explained by his background as a businessman. By focusing on a way to make a living, he has to come up with his own business model, which according to him, if successful, would benefit not only him but also the villagers. He described his project in detail, saying that it is the kind of model that would contribute to a fair distribution of wealth. In other words, it would enable participating villagers to establish themselves.

“(In the current political climate) there is no use talking. It’s just like hitting a wall. What we need to think about now is how to empower our fellow red shirts; how to help them make a living. The economy does matter. Many political activists fail because they are too extreme to the point that they simply ignore the importance of it, but it is highly essential for villagers,” insists Ajarn Toi.