Although Thailand is usually thought of as a recipient, not exporter of pop culture, Thai soap operas are making waves in mainland China.

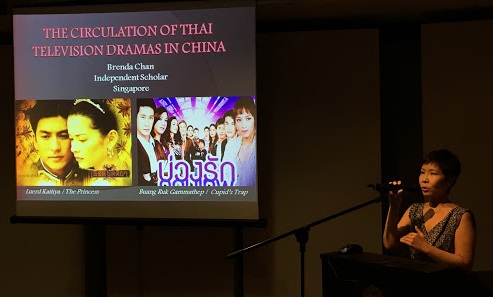

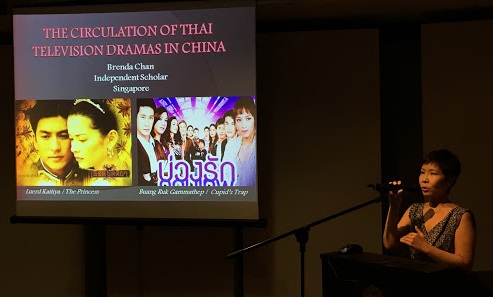

Brenda Chan, and independent Singaporean scholar who studied at Nanyang Technological University, gave a lecture titled “The Circulation of Thai Television Dramas in China” at The Siam Society on 18 March 2016 as part of their 2015–2016 Lecture Series.

While Thailand is typically thought to be on the receiving end of imported pop culture, especially from East Asian nations like Japan and Korea, this asymmetrical cultural flow is showing signs of reversing, says Chan, through the popularity of Thai soap operas (lakorn) in mainland China.

Brenda Chan lecturing on “The Circulation of Thai Television Dramas in China”

The prominence of Thai lakorn rather than Thai films in China is due to the state quota of only allowing 20 foreign films (in addition to 14 IMAX films) per year to be screened officially—most of which are Hollywood films. Therefore, any prominence that Thai films have gained in China is through online channels. Thai films that have become popular through online streaming include the 2007 gay romance film Love of Siam and the 2009 lesbian romance Yes or No, so much so that the lead stars of these films have gained quite a fan following in China.

Mainstream channels are more free to broadcast soap operas, while the number of foreign imports is still limited. The initial wave of lakorn popularity in China was in 2009–2011, beginning when “Battle of Angels” (สงครามนางฟ้า, about female air hostesses fighting over male pilots) was broadcast on Anhui Satellite TV. The popularity and prices of Thai lakorn rose to be on par with Hong Kong dramas. However, due to tightening state controls on broadcasting foreign media, censorship (the homosexual subplot of “Battle of Angels” was completely cut out), and viewers being able to identify clichéd elements of lakorn, the first wave petered out. Alas, hopeful headlines at the time, such as “cooling of the Korean wave, rise of the Thai sun,” did not pan out, as interest in Korean drama was renewed, said Chan.

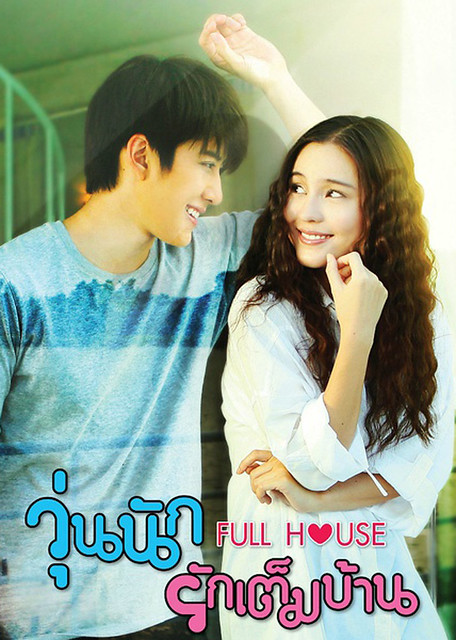

However, with the release of Full House Thailand in 2014, Chinese interest in Thai lakorn was renewed, and the second wave washed over China's streaming sites. Full House Thailand, with its trendy look that attracted younger viewers, was a “lakorn that doesn’t look like a lakorn,” said Chan. Even the story itself, about a woman and a male superstar who fall in love after they are forced to live together, was a remake of the Korean original of the same name released in 2004.

Full House Thailand became as popular as the hit K-drama at the time, My Love From the Stars, says Chan. In fact, the lead actor of Full House Thailand, Mike Pirat, performed at the 14th Top Chinese Music Awards in Shenzhen due to popular fan demand and has even begun to act in Chinese soap operas too, such as Love Jewellery. Exclusive streaming rights for Full House Thailand were bought by Tencent Video, a Chinese video streaming site.

Still, Chinese lakorn fans whose thirst for drama has not been satiated by limited state broadcasts turn to online fansubbing groups. Fansubbing is a practice where enthusiastic fans obtain foreign cultural products, translate the text, then release subtitles for viewing, without asking for permission from the copyright holders (Lee 2011).

Fansubbers, through their sheer passion, dedicate multiple hours of unpaid labour to popularize lakorn (taking three to four hours to translate a 46-minute episode, for example), working in teams and racing with other groups to release high-quality subtitles as fast as possible.

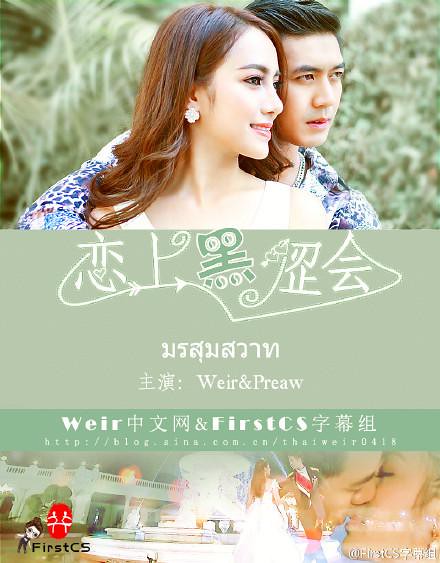

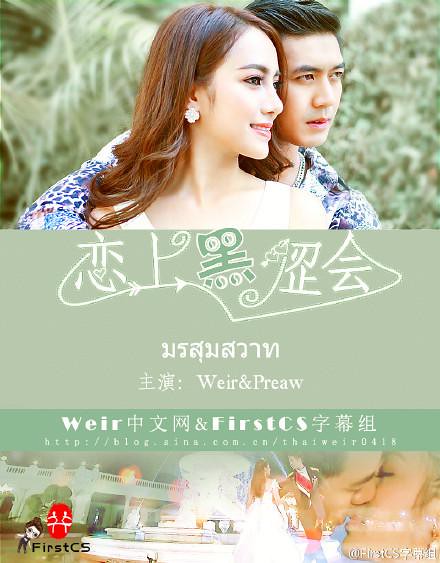

Poster of Chinese subtitling group First CS advertising their subtitles for the lakorn “Morasoom Sawat” (Source)

Poster of Chinese subtitling group First CS advertising their subtitles for the lakorn “Morasoom Sawat” (Source)

There are 16 main subtitling groups for lakorn on Chinese video sharing websites, each with their own official channels and even branding. For example, a group may attach their logo to all of their videos and release posters of an upcoming fansubbed lakorn. These fansubbing groups indigenize the cultural product through their translations, such as by adding local meanings and internet slang to the subtitles. Fansubbing groups are so dedicated that fans with different skills team up and pool their abilities, such as language or technical skills, into a form of collective intelligence (Jenkins and Levy), to make their beloved lakorn available to local viewers at high quality.

The circulation of Thai TV dramas in China exemplifies media convergence, where old and new media, grassroots and corporate, and even producer and consumer collide (Jenkins 2006). In the case of China, says Chan, the state’s power is also a huge factor. Continued penetration of Thai lakorn into the Chinese market may be compromised by new state rulings that require online streaming sites to send foreign dramas to the government for approval before they can be uploaded, says Chan. Plus, there has not been a lakorn after Full House Thailand to significantly sustain the momentum of a cultural “Thai Wave”... yet.

Chinese subtitles for the 2008 lakorn “Jam Loey Ruk” (จำเลยรัก), a huge hit among Chinese netizens that propelled the creation of fan communities for “Aum” Atichart Chumnanon (Source: ATM Chinese Fanclub)

Chinese subtitles for the 2008 lakorn “Jam Loey Ruk” (จำเลยรัก), a huge hit among Chinese netizens that propelled the creation of fan communities for “Aum” Atichart Chumnanon (Source: ATM Chinese Fanclub)

As for why Thai lakorn in particular may have found an audience in mainland China, a 2011 survey on Weibo (China’s popular microblogging service) by the Royal Thai Consulate found that the most appealing aspects for Chinese audiences are 1) beautiful scenery, 2) attractive plots and 3) good-looking actors and actresses, whose often bi-racial features were perceived as more exotic than say, Korean actors and actresses.

A Chinese audience member contributed to Chan’s lecture, saying that lakorn really opened a window to Thailand for Chinese audiences. By seeing images of Thailand’s cities, the beautiful people, and the scenery, the Chinese audiences started to see Thailand as part of modern urban Asia, and not backwards as previously thought. Interestingly, there is much less mass interest in watching historical Thai lakorn than ones set in modern times. “We feel closer to Thailand when watching these lakorn,” she said, “and it makes us want to visit.”

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Lee, H. (2011). Participatory media fandom: A case study of anime fansubbing. Media, Culture & Society, 33(8), 1131-1147.