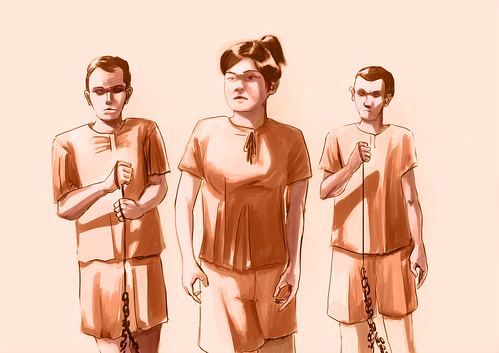

Prisons in Thailand still fail to recognise the basic rights of female prisoners, depriving women of essential health services and goods from sanitary pads to bras. Overburdened prisons due to Thailand’s harsh drug laws aggravate the current situation. This report reveals the devastating condition of female prisons in Thailand, places where women detainees live without dignity.

Fungus infested bras and unchewable food

During my visits to prisons, female prisoners told me they receive bras through donations from outsiders. Oversized and so old they are no longer elastic, those bras are home to different types of fungus.

“Whenever they give out bras, we will all go crazy,” said Tick, an inmate. “Bras are usually distributed by room but [what bra you get] also depends on whether you have any connection to the room leader. If you don’t get along well with the room leader, you will get the leftover bras without a chance to choose. Often I always get bras and pants that are too large, so I have to give them away.”

“The same goes for sanitary pads. We have to sign a form before getting a pack. They are bad quality and barely have any glue. When we wear them, sometimes we have to use rubber bands to hold them against our underwear,” said Tick. “One time, a prisoner was running and the pad just dropped out onto the middle of the exercise field. When I have money, I’ll buy branded items because they are much better.”

Since money is required to access basic goods in prison, incarceration can create financial strife for inmates who rely on borrowing.

“We can withdraw a maximum of 300 baht per day, an increase from the previous 200 baht maximum. I cannot live on that small amount so I have to take loans ‘from the inside’. But the interest rate is 20 per cent per four days,” said another prisoner Pla. “There are so many creditors-cum-prisoners who have gotten quite rich. Some have about 200,000 baht in their bank accounts and manage to send back home 50,000–60,000 baht per month. Even though the authorities are aware of this, they don’t really want to intervene. If the borrowers do not have the money to pay back, the foodstuffs sent by their relatives are confiscated.”

“As for work, sometimes we have to do jobs like rolling cigarettes or folding gold leaf used in temples. Each worker needs to produce 400–600 pieces per day to earn about 100 baht every 3-4 months,” she says. “Who said one doesn’t need money in prison? You do need money to survive.”

As for food, she asks me if I have ever had ‘cold water mama’: instant noodles with cold water since the prison doesn’t provide hot water. Food in prison is repetitive and of low quality. She once ate porridge with chicken feet and pork so gummy that she couldn’t chew.

That was the situation before the junta came into power in 2016. After that, they were barred from even cooking.

NCPO reforms for the worse

After the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) seized power in May 2014, the Department of Correction that administers Thailand’s prisoners was affected heavily. The result was new restrictions on prisoners’ lives.

“The front of the sleeping room states that it has the capacity for 30–33 persons. But when I arrived there, 77 people were sleeping in that room. Of course, I couldn’t sleep. In the second year, there were about 58 people. After the 2014 coup, they told us to return the blankets relatives had brought us but we wouldn’t let them,” said Pla.

Auyphon Suthonsanyakorn, the facilitator of the ‘From Heart to Heart’ program that works on the long-term rehabilitation of female prisoners, told Prachatai that women have faced many new challenges in prison since the NCPO came into power.

“They have ordered female prisoners not to take anything up to the sleeping hall. They are only allowed to take three pieces of tissue paper with them. But women have specific needs: some are on their period, some wear glasses. They are also barred from taking books. Some women like to write in their diaries and some read prayer books before going to bed,” she said. “But the NCPO gave a sweeping order to prevent any of that. Prison guards told me they are afraid of being found guilty if they don’t follow the orders.”

“The NCPO wants to be strict on drugs. Initially they also barred [the women] from bringing drinking water [to the sleeping hall]. They were not okay with that so we negotiated, and they were allowed to bring a bottle of water plus five pieces of tissue paper, which was later reduced to three. Even though we don’t have a drug problem, we cannot decide things ourselves. This is because of the sweeping orders. NCPO said if the prison wouldn’t tackle it, they would do it themselves. That’s why the prison authorities are afraid and have to impose these strict rules on the prisoners.

No health services, just paracetamol

Women prisoners are entitled to health services from the state. They are entitled to access public health services under the national health security scheme like any other citizens. But since prisons are overburdened and underfunded, the solution for women prisoners in reality is to simply ‘not get sick.’

“Inside, they always said do not get sick because you only ever get paracetamol to cure everything,” she said.

In some cases, prisoners face verbal abuse from health professionals. In the case of Tick, who returned to prison after giving birth, she had to see the doctor inside the prison.

“The stitch that I had got infected. I told a male doctor that but he didn’t even bother to look at it,” said Tick. “He said it’d be fine and gave me paracetamol.”

“He is the in-house doctor there and couldn’t be more rude. When he examined my record, he asked me, ‘How did you get pregnant when you’re so ugly?’. He also asked if the child has a father, or if I was sleeping around. I was so pissed off I cursed back at him. I got punished for that.”

Women prisoners who live within a smaller compound within a larger male prison face even more problems than those in women’s correctional institutes or in the women’s sections of large central prisons. This is because women prisoners in male prisoners do not have their own medical unit, but have to share services male inmates. They are given access to health services only after male inmates are finished, due to prison regulations that male and female prisoners are not allowed to mingle.

Auyphon said doctor’s visits in women’s prison are rare. “Once a week is considered very generous. If it’s a central prison, he may only enter the male inmate zone. The female prisoners often won’t get to meet with the doctors. In general, there might be one nurse who is always stationed there to look after both male and female prisoners,” said Auyphon.

“I’ve seen a case where a woman inmate got really sick and and could not get up. She was lying there for many days. When I got in that day, she also had a high fever. When I touched her knee, it was really hot and swollen and badly infected. Yet she wasn’t taken to hospital. Some officers agreed it was a serious case, but they didn’t have enough authority .”

Luckily, that inmate’s relatives requested that she be transferred to a hospital when she could not bring herself to meet them. The doctor later said that if she had come to the hospital just a bit later, she might have ended up at her own funeral.

The situation is comparable in central prisons, where women share facilities with male inmates and are not taken to hospital unless the situation is dire. In one such prison, a woman prisoner sprained her leg after falling down the stairs. She was taken to in-prison medicine unit and given some topical cream. The nurse diagnosed that it wasn’t serious so they didn’t take her to hospital.

These days, she still limps. The bone likely fractured but since it never received proper treatment, she now cannot walk properly.

Women correctional institutes are somewhat better. The doctors usually visit once a week. Women can access a wider range of medicines.

When winter hits, women inmates in the north and northeastern prisons have to suffer under the cold weather. Usually they are given three blankets per person to be used as a pillow, blanket and a mattress respectively. In winter however, that is not enough.

“Before that wewere given five blankets per person. The authorities also allowed relatives to buy more for them. After the allowance was reduced to three pieces, the prisoners protested. The directors then filed a request to make the prisoners get five pieces. The thing is that in winter, even five is not enough because they are bad quality. But they cannot provide more because the prisons have a tight budget.”

...............

Chartchai Suthiklom, the former director of the Department of Correction — now a National Human Rights Commissioner — said that in principle, prisons are obliged to provide basic necessities to prisoners.

The ‘Prisoners’ Manual’ published on the prison’s website states that inmates are entitled to:

- The right to get food that is nutritious and fulfils the body’s needs. The Department of Correction guarantees that every prisoner will receive three meals a day for free from the first day they enter prison until the last day.

- The right to clothing suitable to the weather. Many inmates may have their own clothing from relatives. For those who cannot get their own, prison authorities should provide them with personal items, including clothes and blankets.

- The right to hygienic conditions. All prisons are obliged to provide a hygienic sleeping area for inmates.

- The right to receive free health care. Every prison has its own medical facilities and nurses that should provide appropriate care to the inmates. If the inmate is seriously ill, he/she may be sent to an external hospital or sent to the prison’s hospital in Bangkok.

Despite these regulations, it’s clear that the reality does not reflect the ideals.

...............

Why is it that prisons are overflowing with inmates? Does it mean that our society has more criminals or bad people than others? Or is there something wrong with our justice system?

Are atrocious prison conditions the fault of the Correction Department or the prisons? Obviously both share some responsibility. Yet prisons are just small jigsaws in the bigger picture of an inefficient justice system. Problems faced by female prisoners do not derive solely entrenched hierarchies within the prisons, they are caused at root by the Correction Department’s measly budget.

84.58 per cent of female inmates were sentenced from drugs cases. As of 1 June 2016, out of 35,768 convicted criminals, 30,821 were convicted from violating drug laws.

It is obvious that Thailand’s overly harsh drug laws are putting more and more people into sub-par prisons.

Note: This article was originally published on Prachatai Thai. It was translated from Thai to English by Suluck Lamubol.